-40%

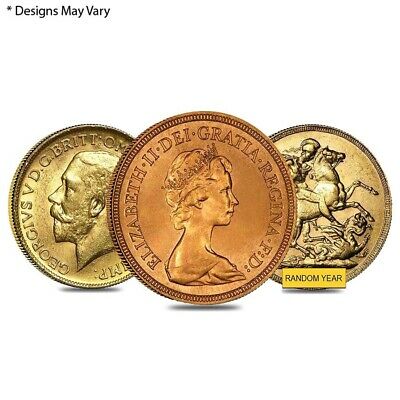

1793, Great Britain, George III. Rare Gold Guinea Coin. Better Date! NGC MS-61!

$ 1431.22

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

CoinWorldTV1793, Great Britain, George III. Rare Gold Guinea Coin. Better Date! NGC MS-61!

Mint Year: 1793

Denomination: Gold Guinea

Reference: S-3729, Friedberg 356, KM-609.

R!

Condition:

Certified and graded by NGC as MS-61!

Material: Gold (.917)

Diameter: 23mm

Weight: 8.36gm

Obverse:

Laureate head of George III right.

Legend: GEORGIVS . III - DEI . GRATIA .

Reverse:

Crowned quartered British shield. Date in legend below.

Legend: .M.B.F.ET.H.REX.F.D.B.ET.L.D.S.R.I.A.T.E.ET.E.1793.

Authenticity unconditionally guaranteed

.

Bid with confidence!

George III

(George William Frederick; 4 June 1738 - 29 January 1820 [N.S.]) was King of Great Britain andKing of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of these two countries on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until his death. He was concurrently Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and prince-elector of Hanover in the Holy Roman Empire until his promotion to King of Hanover on 12 October 1814. He was the third British monarch of the House of Hanover, but unlike his two predecessors he was born in Britain and spoke English as his first language. Despite his long life, he never visited Hanover.

George III's long reign was marked by a series of military conflicts involving his kingdoms, much of the rest of Europe, and places farther afield in Africa, the Americas and Asia. Early in his reign, Great Britain defeated France in the Seven Years' War, becoming the dominant European power in North America and India. However, many of its American colonies were soon lost in the American Revolutionary War, which led to the establishment of the United States of America. A series of wars against revolutionary and Napoleonic France, over a 20-year period, finally concluded in the defeat of Napoleon in 1815.

In the later part of his life, George III suffered from recurrent and, eventually, permanent mental illness. Medical practitioners were baffled by this at the time, although it has since been suggested that he suffered from the blood disease porphyria. After a final relapse in 1810, a regency was established, and George III's eldest son, George, Prince of Wales, ruled as Prince Regent. On George III's death, the Prince Regent succeeded his father as George IV. Historical analysis of George III's life has gone through a "kaleidoscope of changing views" which have depended heavily on the prejudices of his biographers and the sources available to them.

George III lived for 81 years and 239 days and reigned for 59 years and 96 days-both his life and his reign were longer than any of his predecessors. Only George's granddaughter Queen Victoria exceeded his record, though Elizabeth II has lived longer.

George III was dubbed "Farmer George" by satirists, at first mocking his interest in mundane matters rather than politics but later to contrast his homely thrift with his son's grandiosity and to portray him as a man of the people. Under George III, who was passionately interested in agriculture, the British Agricultural Revolution reached its peak and great advances were made in fields such as science and industry. There was unprecedented growth in the rural population, which in turn provided much of the workforce for the concurrent Industrial Revolution. George's collection of mathematical and scientific instruments is now housed in the Science Museum (London); he funded the construction and maintenance of William Herschel's forty-foot telescope, which was the biggest ever built at the time. Herschel discovered the planet Uranus, which he at first named after George, in 1781.

George III himself hoped that "the tongue of malice may not paint my intentions in those colours she admires, nor the sycophant extoll me beyond what I deserve", but in the popular mind George III has been both demonised and praised. While very popular at the start of his reign, by the mid-1770s George had lost the loyalty of revolutionary American colonists, though about half of the colonists remained loyal. The grievances in the United States Declaration of Independence were presented as "repeated injuries and usurpations" that he had committed to establish an "absolute Tyranny" over the colonies. The Declaration's wording has contributed to the American public's perception of George as a tyrant. Contemporary accounts of George III's life fall into two camps: one demonstrating "attitudes dominant in the latter part of the reign, when the King had become a revered symbol of national resistance to French ideas and French power" and the other "derived their views of the King from the bitter partisan strife of the first two decades of the reign, and they expressed in their works the views of the opposition". Building on the latter of these two assessments, British historians of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, such as Trevelyan and Erskine May, promoted hostile interpretations of George III's life. However, in the mid-twentieth century the work of Lewis Namier, who thought George was "much maligned", kick-started a re-evaluation of the man and his reign. Scholars of the later twentieth century, such as Butterfield and Pares, and Macalpine and Hunter, are inclined to treat George sympathetically, seeing him as a victim of circumstance and illness. Butterfield rejected the arguments of his Victorian predecessors with withering disdain: "Erskine May must be a good example of the way in which an historian may fall into error through an excess of brilliance. His capacity for synthesis, and his ability to dovetail the various parts of the evidence … carried him into a more profound and complicated elaboration of error than some of his more pedestrian predecessors … he inserted a doctrinal element into his history which, granted his original aberrations, was calculated to project the lines of his error, carrying his work still further from centrality or truth." In pursuing war with the American colonists, George III believed he was defending the right of an elected Parliament to levy taxes, not seeking to expand his own power or prerogatives. Today, scholars perceive the long reign of George III as a continuation of the reduction in the political power of monarchy, and its growth as the embodiment of national morality.

Only 1$ shipping for each additional item purchased!